Bubbling In The 90S

-

Music

-

Music

Rotterdam, any weekend circa 1994. Near the docks, a club called Imperium is packed with hundreds of Dutch youth, almost all of them of Afro-Caribbean or Surinamese descent. The DJ is playing dancehall music, and although any reggae fan would recognise the guitar melody from Taxi Gang’s ‘Santa Barbara’ riddim – AKA ‘Murder She Wrote’ – running through the mix, the tempo is way up compared to that of the sound of Jamaica. This is a bubbling party, where 33 rpm grooves go up to 45 rpm and the pitch slider on the turntables get maximum usage.

That same weekend in Rotterdam, 3 kilometers away, a sports hall called Energiehal is also packed with thousands of – mostly white – Dutch youth partying to fast music. This scene is called gabber and the dancing couldn’t be further removed from the movement at Imperium. Where the wide-eyed gabbers perform a stiff dance called hakken, the most accomplished bubbling dancers slide across the floor (or better yet the stage, with Amsterdam vs Rotterdam competitions a popular draw) with the loosest of limbs, a most fluid take on body-popping. Boys and girls grind against each other in a display of simulated sex while the BPM hits up to 140, with occasional moments of respite when a reggae or R&B tune in its natural tempo is allowed to calm proceedings.

In contrast to the gabber scene, which has been documented extensively as the first truly native Dutch youth subculture, the contemporaneous bubbling style has at times almost vanished from the collective memory, despite mass popularity across the Netherlands in the mid-1990s and going on to become a formidable influence on the development of the popular ‘Dutch house’ style of the 2000s and, by extension, EDM. The main reason for this is probably the fact that bubbling sound was created in the moment by club DJs, the most important being Moortje, who returned to Holland in the late ’80s after a few years of DJ’ing in Curaçao, a former Dutch colony in the Carribean. There are no classic early bubbling productions, because they were in-the-moment results of the DJ’s creativity: Moortje pitching up dancehall hits like Shabba Ranks’ ‘Trailer Load of Girls’, MCs Pester and Pret hyping up the crowd even more. DJ mixes sold on cassette tapes were very popular and dubbed many times over in the ’90s, but few of them have survived online into 2020.

It’s not until the end of the decade, after the scene has more or less died down, that young house producers like Chuckie, who cut his teeth under bubbling DJ Memmie, start to produce dance tracks that are heavily influenced by bubbling. Bubbling Beats, a CD mixtape series from a teenage DJ who will go on to be voted the number one DJ in the world a decade later, Hardwell, takes the sound truly mainstream in the 2000s by including samples and melodies from pop and trance music. That decade, Dutch DJs like Chuckie, Afrojack and The Partysquad, who have grown up with bubbling, develop a style called Dutch house with a galloping rhythm that can readily be traced back to the sound of popular bubbling DJs like Moortje, Memmie, Funk, Chippie, Coversquad, Massive and others. Diplo takes a fancy to it, and in just a few years this amalgam of house, bubbling, trance and a pinch of gabber transforms into EDM.

By the mid-2010s bubbling music is gaining the critical recognition it lacked in its heyday. DJ Moortje and MC Pester are reunited for the first time in years at Rotterdam’s Buma Beats festival in 2013, and in 2016 the successful Dutch hip-hop record label Top Notch produces a 45-minute documentary on bubbling, DJ Moortje and MC Pester called Bandje 64, which is eventually broadcast on national TV. An attempt at a comeback for Moortje and Pester stalls after a single, ‘Plakken’, fails to chart. But bubbling refuses to go away. In 2017 DJ Missdevana from Eindhoven releases an EP on the cutting edge electronic label Nervous Horizon from London, that introduces the Dutch bubbling beat to the international bass music diaspora.

The dancers that made up the scene in the ’90s are now adults, many with children of their own. One of them is Randy Telg, co-founder of Bubbling TV. If you look for any kind of bubbling activity happening today, you’ll soon find yourself watching Bubbling TV’s dance clips on various social media. As a young teen, Randy would practice his moves every single day, and show them off on the weekends at the bubbling parties in his local Rotterdam community centre. And while bubbling didn’t last forever, Randy would incorporate the moves into his breakdance routines, which would eventually take him around the world as a dancer. Nowadays he teaches kids all over the Netherlands, although some of them, to his surprise, know the bubbling dance moves as klaksen, unaware of their origins. The kind of bubbling battle dancing that Randy promotes is of course nothing like the sexual grinding and schuren that could be seen (and experienced) on the dancefloors of clubs like Rotterdam’s Imperium, The Hague’s Voltage, Marcanti Plaza in Amsterdam, Carte Blanche in Weert and so many others. The elasticity on display at Bubbling TV is as impressive as ever however, and should the world ever tire of reggaetón’s slow grind, a new generation appears to stand ready to drastically up the tempo.

Bonus piece, A CULT PHENOMENON CALLED BUBBLING:

Related Articles

-

Interview by Passion DzengaAnysia Kym moves like someone who grew up inside rhythm. Bronx-born and now Brooklyn-based, she’s a drummer, producer, singer, and songwriter whose work refuses the neat genre categories the industry loves to sell back to Black femmes—especially those who are multi-instrumentalists. Kym’s music is a living archive of the sounds that raised her: the radio-fuelled hip-hop and R&B household, the mixtape culture that shaped uptown New York, and the deep Black musical lineage embedded in sampling. “Aside from a heavy percussive element, my production almost always involves sampling,” she explains, framing it not as a production trick but as an art form with roots that stretch far beyond any single era of rap. That history is audible in the technical language of her tracks—blues and funk residue, breakbeat architecture, jagged drum patterns, and time signatures that shift the ground beneath you, sometimes landing in 6/4 like a deliberate refusal to be easily consumed.If her production work is maximal in texture—built from self-arranged compositions, samples, live drums, or all three—her songwriting practice often moves in the opposite direction. In demos, she leans into minimalism: lyrics first, guitar-led sketches, a quieter space where voice and intention can sit in the foreground. This two-lane approach is not indecision; it’s a method. Each project becomes a different solution to the same problem: how to deconstruct the limitations placed on her body and her talent by choosing which of her abilities to centre, and refusing to let any single lane define the whole story.That rapid evolution has been visible for years, from her drumming period with the emo-tinged indie band Blair to solo releases that slide between hip-hop and electronica with a producer’s precision—most notably Truest (2024). There’s also an undeniable pull toward UK continuum energy in her work: jungle and drum’n’bass DNA as a spiritual cousin to London’s scene, made tangible on Pressure Sensitive (2023), her collaboration with British rapper and 10k label-mate Jadasea. But it’s her recent project Purity—made with producer Tony Seltzer—that distils Kym’s current language into something sharp, compact, and strangely intimate: a suite of short tracks engineered with clocklike exactness, where pitched-up vocals become percussion, and songs end before they over-explain themselves. In our conversation, Kym describes the process as deliberately organic—less “let’s make a genre record” and more a studio dialogue that kept getting weirder, freer, and more honest the longer it went on. What emerges is an artist learning, in real time, how to protect her curiosity—how to collaborate without compromise, how to let desire and longing live in the music without turning it into performance, and how to stay in control of the narrative when visibility arrives. We caught up with Kym to talk about sampling as lineage, drums as instinct, minimalism as discipline, and why, sometimes, the strongest statement a song can make is knowing exactly when to stop.For those who might be discovering you for the first time, can you introduce yourself and where you’re from?I’m from the Bronx, New York — specifically Co-op City. I live in Flatbush now, in Brooklyn. I’m a producer, songwriter, and singer. I used to play drums in a band, and over the last few years I’ve been focusing more on production and songwriting.Growing up in the Bronx comes with a lot of musical history. What were you surrounded by early on?I wouldn’t say I had specific artists I consciously thought of as influences back then, but music was always present. Both my parents are from uptown — Harlem and the Bronx — and they listened to a lot of Hot 97 back when it was very different from what it is now. My mom loved artists like The Lost Boyz and Slick Rick. My older brother was really into mixtape culture — buying tapes, bootlegs, the whole thing. That culture was everywhere: barbershops, hair salons, people selling tapes out of backpacks. Music felt communal and accessible.Hip-hop and R&B were the backbone of our household. And in New York, especially uptown, musicians didn’t feel distant. You might see someone on TV, but you might also see them at a family barbecue. That closeness definitely shaped my curiosity, even though the music I make now is more experimental than what was on the radio.Would you say those sounds raised you?Absolutely. It was a community thing. My parents only really knew uptown New York culture, but they were open-minded. I’m one of four siblings, all very different people, so they kind of had to be. That openness let us explore freely.Were you digging through your parents’ CDs and mixtapes as a kid?For sure. And my older brother babysat me a lot — we’re ten years apart — so I was exposed to everything he listened to. There wasn’t much censorship. I heard the curse words, watched whatever was on TV. My parents trusted us, and that freedom mattered.What was the first music you bought with your own money?The first CD I ever bought was What the Game’s Been Missing by Juelz Santana — from Walmart. I didn’t realise at the time that Walmart didn’t sell explicit music, so I ended up with the clean version. Meanwhile, my brother had the gritty mixtape versions. I was confused listening to all the bleeps. Alongside that, I loved Raven-Symoné, Bow Wow, The Cheetah Girls, Aaliyah, and Amerie — a wide mix. But Juelz was technically my first.Your music today leans heavily into percussion, breakbeats, and unconventional rhythms. How did that develop?Before I played drums, I actually started producing — very badly — on FL Studio. That was my first taste of making music myself. From there, I became obsessed with drums and wanted to understand the instruments behind the sounds I was sampling. I bounce back and forth between live music and production constantly. I don’t think you can really separate the two, especially in hip-hop.A lot of it came from hip-hop and R&B, pulling from everywhere — jazz, gospel, Latin music, Brazilian and West African music. All of it eventually gets shaped into something rhythmic. Being in bands also exposed me to odd time signatures and math-rock ideas. And honestly, a lot of it is trial and error. I don’t always know what I’m doing — happy accidents are a huge part of my process.Your tracks often feel loop-driven but very intentional. How do you know when a musical idea is finished?It’s very feeling-based. When I was only making instrumentals, the beat was the song, so it could just live in a loop. Writing vocals changed that. If it’s something I plan to sing or have someone else write to, I leave space. I treat instrumental tracks differently from songwriting tracks. What “finished” means depends on the purpose of the song.You moved from FL Studio to Ableton fairly early on. What shifted for you there?Ableton felt more intuitive, especially coming from a band context. It allows you to think like a performer, not just a beat-maker. There’s so much depth to it — I probably use only a fraction of what’s possible — but it opened things up in a way FL didn’t for me.You’ve collaborated with artists like Tony Seltzer and Loraine James. What do collaborations reveal to you about yourself?I need to feel safe creatively. Collaboration works best when it’s not a one-off moment, but something you’d want to return to. With Tony and Loraine, there’s a shared openness to getting weird. There’s no pressure to hit a specific genre or outcome. We stopped trying to say “let’s make this kind of track” because it killed the fun. The best moments came from conversation, not intention.Loraine, especially, has been producing longer than I have, and she’s a real nerd about sound — in the best way. She listens to everything, plays with time signatures, and still has a very clear identity. That inspires me because I’m still discovering my sound, and I don’t think that’s something you can plan. It develops naturally.On Purity, there’s a lot of sped-up vocals. What does that choice mean to you?Sped-up vocals take the focus away from identity and put it on movement and feeling. The voice becomes another instrument. It’s less about who’s singing and more about how it hits. That anonymity is freeing. It connects to jungle and garage traditions too — vocals as texture, not centre stage.Many tracks on the record are under two minutes. Why that restraint?It was intentional. The first song we made was longer and more traditional, but once we started making shorter songs, they just felt right. Even though we’re in a maximalist era, not every idea needs to be stretched. Some songs hit harder because they end where they do. Short doesn’t mean incomplete.You’re no longer in a band and are working more as a solo artist. What does that shift give you emotionally?It feels childlike again — like a one-woman band. I’m experimenting more, playing guitar, producing, writing, all from home. I want music-making to feel playful. If it stops feeling that way, it loses its appeal.You don’t seem to set many technical limitations in your process. Where do you draw boundaries?The main limitation I set is who I work with. Visibility brings opportunities, but not all collaborations are about the music. I’m careful about that. I want to avoid being boxed in — especially as a Black woman — whether that’s hypersexualisation or aesthetic over substance. Controlling my narrative matters.You danced on camera in the “Speedrun” video. Do you see the body as another instrument?In performance, yes. For that video, I wanted to dance specifically because I’m not a dancer. I worked with a choreographer so it felt intentional, not lazy. It wasn’t about perfection — it was about awkwardness, discomfort, beauty, and movement. That’s how life feels to me, and the song captured that.Are there any scenes or sounds you’re exploring right now?I’m inspired by younger producers like Step Team from New Jersey — really wild, unquantized drum patterns. Baby Osama too. But honestly, I also live in the past. I’ve been stuck on Teena Marie for years because that’s what my mom played nonstop. Looking back is just as important as looking forward.DJing has also entered your practice. How does that inform your music?I respect DJing deeply. It’s a craft. I only DJ occasionally because I know how demanding it is — physically, mentally, emotionally. DJs shape spaces for hours at a time, regardless of crowd size. That seriousness inspires me, even though my main practice is still producing and songwriting.Finally, where are you heading next?Early 2026 is hermit mode. I’m working on my next solo project, mostly at home — getting weird, experimenting, writing. I might play a couple of shows in the spring, but the focus is on making the next record feel honest and expansive. I’m excited about that.

Interview by Passion DzengaAnysia Kym moves like someone who grew up inside rhythm. Bronx-born and now Brooklyn-based, she’s a drummer, producer, singer, and songwriter whose work refuses the neat genre categories the industry loves to sell back to Black femmes—especially those who are multi-instrumentalists. Kym’s music is a living archive of the sounds that raised her: the radio-fuelled hip-hop and R&B household, the mixtape culture that shaped uptown New York, and the deep Black musical lineage embedded in sampling. “Aside from a heavy percussive element, my production almost always involves sampling,” she explains, framing it not as a production trick but as an art form with roots that stretch far beyond any single era of rap. That history is audible in the technical language of her tracks—blues and funk residue, breakbeat architecture, jagged drum patterns, and time signatures that shift the ground beneath you, sometimes landing in 6/4 like a deliberate refusal to be easily consumed.If her production work is maximal in texture—built from self-arranged compositions, samples, live drums, or all three—her songwriting practice often moves in the opposite direction. In demos, she leans into minimalism: lyrics first, guitar-led sketches, a quieter space where voice and intention can sit in the foreground. This two-lane approach is not indecision; it’s a method. Each project becomes a different solution to the same problem: how to deconstruct the limitations placed on her body and her talent by choosing which of her abilities to centre, and refusing to let any single lane define the whole story.That rapid evolution has been visible for years, from her drumming period with the emo-tinged indie band Blair to solo releases that slide between hip-hop and electronica with a producer’s precision—most notably Truest (2024). There’s also an undeniable pull toward UK continuum energy in her work: jungle and drum’n’bass DNA as a spiritual cousin to London’s scene, made tangible on Pressure Sensitive (2023), her collaboration with British rapper and 10k label-mate Jadasea. But it’s her recent project Purity—made with producer Tony Seltzer—that distils Kym’s current language into something sharp, compact, and strangely intimate: a suite of short tracks engineered with clocklike exactness, where pitched-up vocals become percussion, and songs end before they over-explain themselves. In our conversation, Kym describes the process as deliberately organic—less “let’s make a genre record” and more a studio dialogue that kept getting weirder, freer, and more honest the longer it went on. What emerges is an artist learning, in real time, how to protect her curiosity—how to collaborate without compromise, how to let desire and longing live in the music without turning it into performance, and how to stay in control of the narrative when visibility arrives. We caught up with Kym to talk about sampling as lineage, drums as instinct, minimalism as discipline, and why, sometimes, the strongest statement a song can make is knowing exactly when to stop.For those who might be discovering you for the first time, can you introduce yourself and where you’re from?I’m from the Bronx, New York — specifically Co-op City. I live in Flatbush now, in Brooklyn. I’m a producer, songwriter, and singer. I used to play drums in a band, and over the last few years I’ve been focusing more on production and songwriting.Growing up in the Bronx comes with a lot of musical history. What were you surrounded by early on?I wouldn’t say I had specific artists I consciously thought of as influences back then, but music was always present. Both my parents are from uptown — Harlem and the Bronx — and they listened to a lot of Hot 97 back when it was very different from what it is now. My mom loved artists like The Lost Boyz and Slick Rick. My older brother was really into mixtape culture — buying tapes, bootlegs, the whole thing. That culture was everywhere: barbershops, hair salons, people selling tapes out of backpacks. Music felt communal and accessible.Hip-hop and R&B were the backbone of our household. And in New York, especially uptown, musicians didn’t feel distant. You might see someone on TV, but you might also see them at a family barbecue. That closeness definitely shaped my curiosity, even though the music I make now is more experimental than what was on the radio.Would you say those sounds raised you?Absolutely. It was a community thing. My parents only really knew uptown New York culture, but they were open-minded. I’m one of four siblings, all very different people, so they kind of had to be. That openness let us explore freely.Were you digging through your parents’ CDs and mixtapes as a kid?For sure. And my older brother babysat me a lot — we’re ten years apart — so I was exposed to everything he listened to. There wasn’t much censorship. I heard the curse words, watched whatever was on TV. My parents trusted us, and that freedom mattered.What was the first music you bought with your own money?The first CD I ever bought was What the Game’s Been Missing by Juelz Santana — from Walmart. I didn’t realise at the time that Walmart didn’t sell explicit music, so I ended up with the clean version. Meanwhile, my brother had the gritty mixtape versions. I was confused listening to all the bleeps. Alongside that, I loved Raven-Symoné, Bow Wow, The Cheetah Girls, Aaliyah, and Amerie — a wide mix. But Juelz was technically my first.Your music today leans heavily into percussion, breakbeats, and unconventional rhythms. How did that develop?Before I played drums, I actually started producing — very badly — on FL Studio. That was my first taste of making music myself. From there, I became obsessed with drums and wanted to understand the instruments behind the sounds I was sampling. I bounce back and forth between live music and production constantly. I don’t think you can really separate the two, especially in hip-hop.A lot of it came from hip-hop and R&B, pulling from everywhere — jazz, gospel, Latin music, Brazilian and West African music. All of it eventually gets shaped into something rhythmic. Being in bands also exposed me to odd time signatures and math-rock ideas. And honestly, a lot of it is trial and error. I don’t always know what I’m doing — happy accidents are a huge part of my process.Your tracks often feel loop-driven but very intentional. How do you know when a musical idea is finished?It’s very feeling-based. When I was only making instrumentals, the beat was the song, so it could just live in a loop. Writing vocals changed that. If it’s something I plan to sing or have someone else write to, I leave space. I treat instrumental tracks differently from songwriting tracks. What “finished” means depends on the purpose of the song.You moved from FL Studio to Ableton fairly early on. What shifted for you there?Ableton felt more intuitive, especially coming from a band context. It allows you to think like a performer, not just a beat-maker. There’s so much depth to it — I probably use only a fraction of what’s possible — but it opened things up in a way FL didn’t for me.You’ve collaborated with artists like Tony Seltzer and Loraine James. What do collaborations reveal to you about yourself?I need to feel safe creatively. Collaboration works best when it’s not a one-off moment, but something you’d want to return to. With Tony and Loraine, there’s a shared openness to getting weird. There’s no pressure to hit a specific genre or outcome. We stopped trying to say “let’s make this kind of track” because it killed the fun. The best moments came from conversation, not intention.Loraine, especially, has been producing longer than I have, and she’s a real nerd about sound — in the best way. She listens to everything, plays with time signatures, and still has a very clear identity. That inspires me because I’m still discovering my sound, and I don’t think that’s something you can plan. It develops naturally.On Purity, there’s a lot of sped-up vocals. What does that choice mean to you?Sped-up vocals take the focus away from identity and put it on movement and feeling. The voice becomes another instrument. It’s less about who’s singing and more about how it hits. That anonymity is freeing. It connects to jungle and garage traditions too — vocals as texture, not centre stage.Many tracks on the record are under two minutes. Why that restraint?It was intentional. The first song we made was longer and more traditional, but once we started making shorter songs, they just felt right. Even though we’re in a maximalist era, not every idea needs to be stretched. Some songs hit harder because they end where they do. Short doesn’t mean incomplete.You’re no longer in a band and are working more as a solo artist. What does that shift give you emotionally?It feels childlike again — like a one-woman band. I’m experimenting more, playing guitar, producing, writing, all from home. I want music-making to feel playful. If it stops feeling that way, it loses its appeal.You don’t seem to set many technical limitations in your process. Where do you draw boundaries?The main limitation I set is who I work with. Visibility brings opportunities, but not all collaborations are about the music. I’m careful about that. I want to avoid being boxed in — especially as a Black woman — whether that’s hypersexualisation or aesthetic over substance. Controlling my narrative matters.You danced on camera in the “Speedrun” video. Do you see the body as another instrument?In performance, yes. For that video, I wanted to dance specifically because I’m not a dancer. I worked with a choreographer so it felt intentional, not lazy. It wasn’t about perfection — it was about awkwardness, discomfort, beauty, and movement. That’s how life feels to me, and the song captured that.Are there any scenes or sounds you’re exploring right now?I’m inspired by younger producers like Step Team from New Jersey — really wild, unquantized drum patterns. Baby Osama too. But honestly, I also live in the past. I’ve been stuck on Teena Marie for years because that’s what my mom played nonstop. Looking back is just as important as looking forward.DJing has also entered your practice. How does that inform your music?I respect DJing deeply. It’s a craft. I only DJ occasionally because I know how demanding it is — physically, mentally, emotionally. DJs shape spaces for hours at a time, regardless of crowd size. That seriousness inspires me, even though my main practice is still producing and songwriting.Finally, where are you heading next?Early 2026 is hermit mode. I’m working on my next solo project, mostly at home — getting weird, experimenting, writing. I might play a couple of shows in the spring, but the focus is on making the next record feel honest and expansive. I’m excited about that. -

Zaylevelten - Guide Pass

Zaylevelten - Guide Pass

Patta SS26 comes with a new visual statement: “Guide Pass” — a music video by Uwana Anthony & Envarka for Zaylevelten.-

Music

-

-

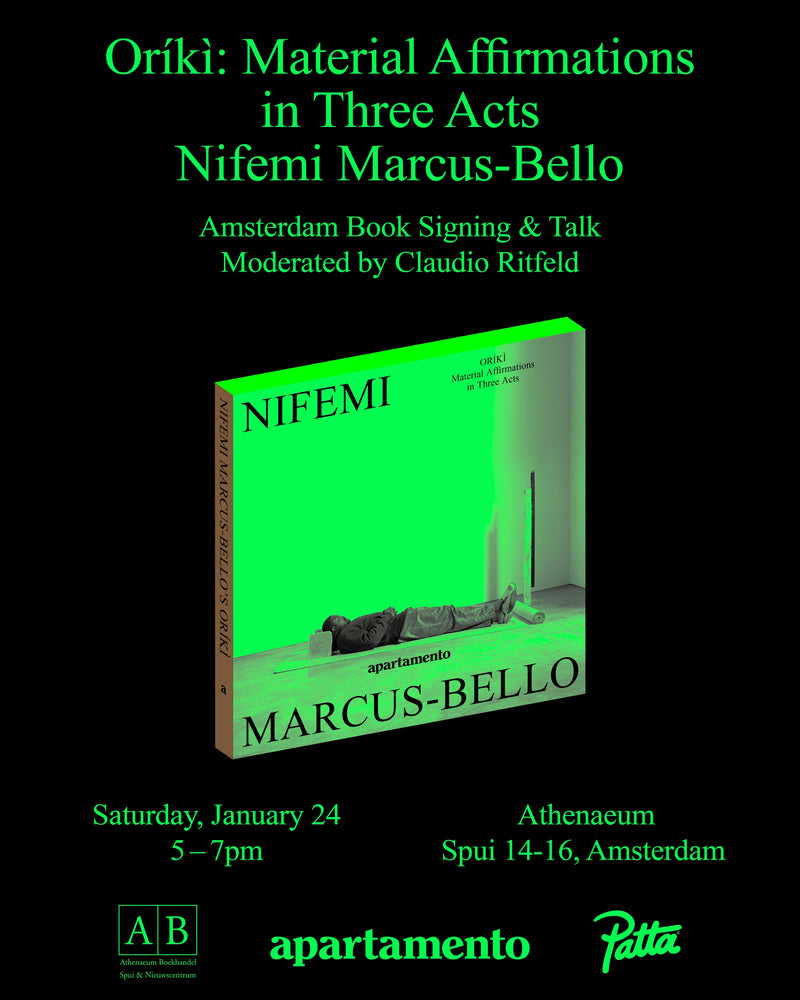

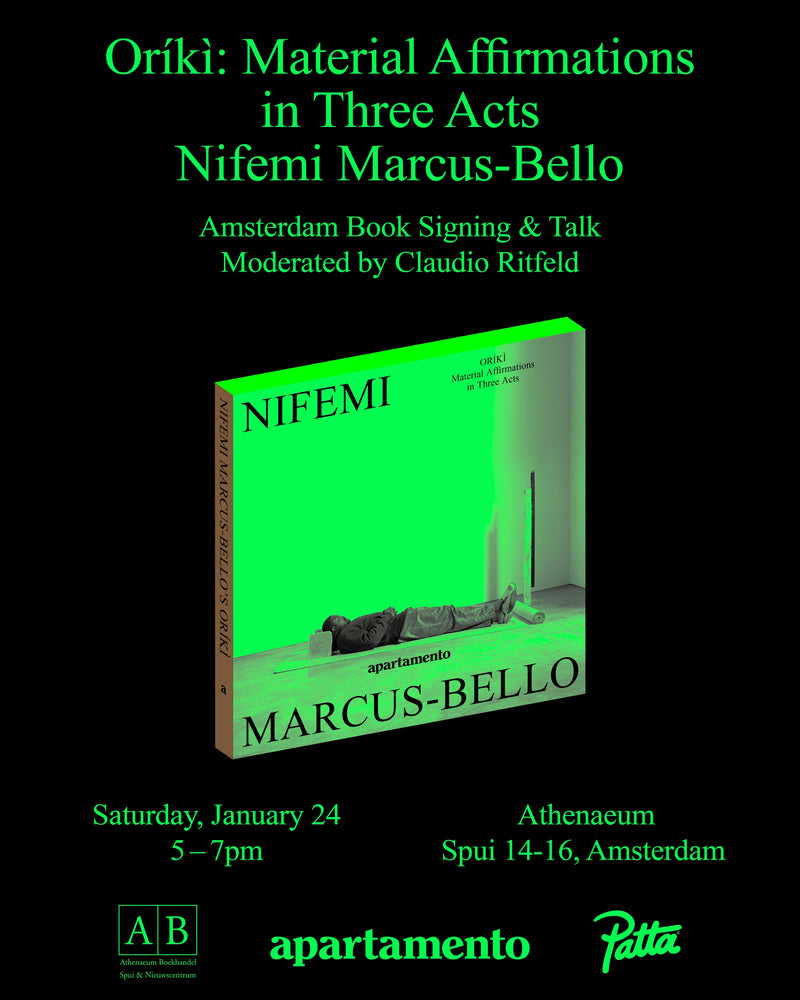

Oriki: Material Affirmations in Three Acts Book Signing

Oriki: Material Affirmations in Three...

We’re excited to invite you to our Amsterdam book signing for Nifemi Marcus-Bello’s ‘Oriki: Material Affirmations in Three Acts’, on Saturday, January 24, at the Athenaeum, with support from Patta and Apartmento. The evening will also feature a live conversation with the artist, moderated by Claudio Ritfeld. Friends in Amsterdam, come listen in, from 5–7pm, meet the artist, and get your copy signed! We can’t wait to see you all there.-

Events

-

-

Alfa Mist - Live at Real World Studios

Alfa Mist - Live at Real World Studios

On Roulette, his sixth studio release, the prolific producer, songwriter, pianist and MC Alfa Mist created a vivid sci-fi universe — a vast dystopia shaped by themes of revenge, forgiveness and redemption. Now, that world is brought into sharp focus in a new video capturing Alfa Mist performing tracks from the record live at Real World Studios.Filmed in the renowned Wiltshire studio complex, the performance strips Roulette back to its emotional core while amplifying its conceptual weight. Alfa Mist’s music has always grappled with big ideas, but here those ideas feel immediate and embodied. Roulette imagines a near-future where reincarnation is discovered to be real — a force connecting dreams, past lives and accumulated knowledge — raising urgent ethical, moral and philosophical questions. In this live setting, those questions resonate with renewed intensity.Across the performance, Alfa moves through selections from the album as if spinning the wheel once more: each track revealing a different character, mood and perspective. His unmistakable signature remains — lambent piano lines, intuitive grooves and moments of free-flowing jazz improvisation — but in the acoustics of Real World Studios, the music takes on a deeper, more cinematic presence. The smoky psychedelia of Roulette feels immersive and tactile, designed not just to be heard but fully felt.The video also highlights some of Alfa Mist’s most ambitious arrangements to date, including passages that glide effortlessly through shifting time signatures. “Life’s not always linear,” he has said — a philosophy that plays out vividly in the fluidity of the live performance.This Real World Studios session underlines Alfa Mist’s position as one of the most forward-thinking composers in UK music today. With melodies that linger long after the final note, the performance captures an artist in constant evolution. As Alfa puts it: “Music is a constant; it’s my state of mind that I keep chiselling and working on.” In this filmed performance, that process is visible, audible and deeply compelling.He performs in Amsterdam at Paradiso on Wednesday, January 28th. Tickets are available now.-

Music

-

-

Get Familiar: $ouley

Get Familiar: $ouley

Photography by Antoine | Interview by Passion DzengaComing out of Bordeaux rather than Paris has shaped $ouley’s music in subtle but important ways. Growing up in a second city, far from the expectations and infrastructure of the capital, he learned early to trust his own instincts and build without permission. Skate spots, bedrooms, video games, and the internet became his classrooms, allowing a sound to form that feels unforced and unconcerned with tradition for tradition’s sake.$ouley’s music draws from a wide emotional and cultural archive—hip-hop and French rap sit alongside Senegalese influences, soul records, video game soundtracks, and the quiet intensity of films like The Wire. Instead of leaning into boom bap or chasing familiar formulas, he moves toward something looser and more future-facing, where feeling leads and genre lines blur.What emerges is an artist driven by intuition and connection: beats that “speak,” visuals shaped through friendship, and live shows that prioritise presence over polish. In this conversation, $ouley reflects on finding his voice outside the spotlight and staying grounded while his world continues to expand.You’re based in Paris now, but you’re originally from Bordeaux. What did it mean to come up in a second city—somewhere that isn’t the capital?Bordeaux is special, but it’s not Paris. It’s not a place where you feel like the industry is waiting for you. If you want to make art there, you have to be strong enough to accept your creativity by yourself first—nobody is going to bring it to you. I grew up in the hood in Bordeaux, and for a long time I was hiding the fact that I even made music.When you say “hiding,” what do you mean?I wasn’t telling people like that. I had my brothers, and they were doing their own thing, and I felt like I had to create my own world. There wasn’t this big city feeling where you can just go somewhere and find a scene instantly. So I kept it private until it started to become real.What was the moment where it started to become real?When I realised people outside my circle were listening. Someone would tell me, “Older people in the city know your name,” or “Somebody’s little brother is a fan.” Then I got invited to perform, and I didn’t even believe it—because I was still figuring myself out. But once you see people really show up, you understand it’s bigger than your bedroom or your phone.With regards to your early influences: family, video games, and building a personal library. What kind of music were you raised on?In the house, it was hip-hop, French rap, US music, and also music from Senegal and Guinea-Bissau like Americo Gomes, because my family is Senegalese. My brothers showed me a lot. My sister too—different things. And I was curious, so I absorbed everything.You also mentioned video games being important.Huge. Video game music helped me build my own library. It’s not just what your family plays—games give you sounds you wouldn’t hear anywhere else. Midnight Club, Gran Turismo, Rockstar games… those soundtracks stayed in my head.Were films part of that education too?Yeah. Old gangster movies, French movies, Disney Channel, The warriors and shows like The Wire. That’s how I discovered Nina Simone. It was like mature music, grown-up music, and it expanded my taste early.From private worlds to publishing music, how did you actually start recording?Skateboarding was a big part of it. I was into Tyler, The Creator and Odd Future, that internet energy. I saw him making music on a MacBook and it made it feel possible. So me and my friends would go downtown and I’d record ideas wherever I could—sometimes even in places like the Apple Store. Before that, I’d already be writing my words down before i even thought about putting it on beats.And then you just started uploading?Exactly. I didn’t overthink it. I uploaded and slowly a small community formed around it. I started on SoundCloud When did you start feeling like you had something to say?It started with writing. I was in private school, but I’m from the hood, so I was seeing different worlds at the same time. I was hearing too much, seeing too much, and it made me want to speak. I did poetry first. Then I started reading my poetry over instrumentals. That’s when I realised I had something—like I wasn’t alone.When did you find your real creative circle?When I met people who had a similar musical education—people who didn’t judge you for doing something new. That’s when studios and sessions started happening more naturally.What’s your writing process now—words first or beat first?Beat first most of the time. Every beat makes me write differently. Sometimes life gives me words first—I write something down, then later a beat matches it. But usually the music speaks to me, and I follow it.Who are the key people around you musically?MH is important—he’s in Paris now but we’re both from Bordeaux. CTP, Deejay Sammy, Gustavio Topman and Yuri Online. We talk music all the time. Then there are people outside France too. I like working across scenes and countries.Do you mess with TTC?Yeah, TTC are legends. They were early with different instrumentals and voice effects in France.Your music is very future-facing. Why did you go that direction instead of classic boom bap?I like new sounds. Artists like Lil B, SGP, Tyler the Creator and the whole internet era showed me you can create a new sound and still be yourself. Hip-hop can have rules—like you have to look a certain way, sound a certain way. Electronic music is more about feeling. I wanted to sound like me. Not like an American version of someone else.What was your first live show like?I was stressed. I couldn’t believe people would pay to see me perform songs I made in such a DIY way. I thought it would be a small crowd, then it was packed. I was nervous and a little too aggressive at first—my friends had to tell me to relax. But now I enjoy it. Now it’s fun.Do you have any pre-show rituals?I check the sound, drink water, listen to my beats. I’m grateful. I close my eyes and just focus.What feels like the next step for you?Travel more, shoot more videos, collaborate more. I have listeners all over the world and I want to meet people in real life, bring the music outside France, and not be afraid of new places.Any dream collaborations?Babyfather would be crazy. And I’d love to do more with people I respect, but timing matters. I want to build real connections, not just chase names.What’s the song that always gets a reaction live?“SUPERFLY (Criminel).” Every time that beat drops, people scream.Why does it have two names?Because in the lyrics I say the way she looks at me is criminal—like she’s sniping me with her eyes. But “Superfly” is the feeling: I’m fly, it’s cinematic, it connects to that movie energy.What’s a more personal record for you?Fever FM is very personal. Songs like “Memory Terio.” And “Party!” too— with the Gran Turismo 4 OST sample. It’s fun but it’s also my real world. Fans told me they played the same game, so it connected deeper than I expected.Your visuals are strong. How do you build that world—covers, videos, the whole language?I have ideas, but it’s also community. I work with friends like Antoine and with people around me. For covers like the Summer Tape artwork, I worked with Julien Marmar—he’s a real artist. For videos, sometimes it’s simple: we see a location, we go, we shoot. We don’t overthink it. When it’s real, people feel it.Can we expect another Summer Tape soon?Maybe later. Right now I want to do something new.Where can people support you?Most of it is on streaming. But I like experimenting with physical drops too—keeping some songs off streaming so the people who really care can find them in a different way.-

Get Familiar

-

-

Get Familiar: Nederland Wordt Beter

Get Familiar: Nederland Wordt Beter

Photography by Karim Sahmi, Zazilie Currie, Dag van Empathie, Luciano de Boterman, Nederland Wordt Beter, New Urban Collective, Mitchell Esajas, Hollandse Hoogte and Raymond van Mil | Graphic by Chayenne van den BrinkIn activism, endings are rare. Movements are often defined by their refusal to stop, by an open-ended urgency that resists closure. To declare an endpoint — to say the work we set out to do is complete — is, in itself, a radical act. That is precisely what Nederland Wordt Beter has chosen to do. From 2010 to 2025, NLWB positioned itself not as a permanent institution, but as a deliberate intervention: a 15-year confrontation with anti-Black racism in the Netherlands, designed with a beginning, a strategy, and a clearly articulated end. On 5 December 2025 — a date long symbolic of exclusion and harm — the movement dissolved itself. Not because racism has ended, but because the goals it set out to achieve have been met. Those goals were neither abstract nor rhetorical. They were concrete, structural, and measurable: the embedding of colonial and slavery history in education; the transformation of the Sinterklaas tradition into an inclusive celebration free from racist stereotypes; and the legal anchoring of the national commemoration of the abolition of Dutch slavery.To understand the significance of this moment, one must understand the discipline behind it. As Jerry Afriyie — poet, organiser, and co-founder of NLWB — explains, the decision to limit the movement to fifteen years was not a concession, but a strategy. Activism without an endpoint risks burnout, dilution, and institutional stagnation. Activism with an endpoint demands clarity: what exactly are we trying to change, and how will we know when we have succeeded? Over fifteen years, NLWB delivered more than 500 lectures across schools, universities, companies, and government institutions. It produced open-access educational materials, teacher guides, activist handbooks, and a historical calendar documenting nearly 200 moments and figures erased from dominant Dutch narratives. It initiated campaigns that reshaped public discourse — from Zwarte Piet Is Racism to #1julivrij — and helped organise the largest anti-racism protests in Dutch history following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. But the most visible impact unfolded in everyday life.Fifteen years ago, Keti Koti — the commemoration of the abolition of slavery — was unknown to most Dutch students. Today, it is nationally broadcast, structurally funded, and legally anchored, with an annual budget of €8 million supporting commemorations across both the European Netherlands and the Caribbean. Slavery history is now mandated in secondary education. Municipalities, museums, and ministries have revised policies, curricula, and public narratives. Apologies once considered unthinkable have been issued by both government and monarchy. Perhaps most symbolically, a tradition long defended as “innocent” has been transformed. Where Blackface once dominated public space each winter, two-thirds of the Dutch population now support moving away from the tradition of Zwarte Piet. Nearly all municipalities no longer subsidise parades featuring racist imagery. What was once normalised has been historicized — relocated, finally, to the past.This transformation did not come easily. The work demanded confrontation, persistence, and personal sacrifice. Afriyie speaks openly about the cost: years of public hostility, professional consequences, physical danger, and time lost with family. NLWB endured surveillance, mischaracterisation, and, at one point, inclusion in a national terrorism assessment — later formally corrected. These were not symbolic battles. They were lived realities. And yet, NLWB refused both martyrdom and vengeance. The movement’s philosophy was pragmatic, not punitive. Justice, not revenge. Structural change, not spectacle. Protest was a means — never the goal. Dialogue mattered, but so did boundaries. Allyship was welcomed, but Black leadership remained non-negotiable. The movement understood that visibility without control risks reproducing the very hierarchies it seeks to dismantle. This is why the decision to dissolve now carries such weight.NLWB does not disappear into silence. Its legacy is deliberately archived — preserved through partnerships with The Black Archives, the Amsterdam City Archives, and public platforms that ensure future access to its materials. Its final exhibition, Netherlands, Do Better! – The Impact of 15 Years of Black Activism, offers not a victory lap, but an invitation: to study what worked, to learn what it cost, and to ask what comes next. The travelling exhibition extends that question across the country, province by province. The theatrical tribute, The Final Word, honours not only visible leaders but the quiet labour of communities who sustained the work. Now, the movement ends not in mourning, but in celebration — a deliberate refusal to let struggle erase joy.In passing the baton, NLWB insists on a final truth: progress is not permanent. It must be protected, renewed, and expanded by those who inherit it. The work does not end because racism has vanished; it ends because responsibility has shifted. As Afriyie reminds us, a country can only do better if its people do better — not just for themselves, but for each other. The measure of this movement is not only what it changed, but what it makes possible. The Netherlands is not finished becoming better. But it is no longer allowed to say it did not know.Who are you — and what are you about?I’m a poet, but for a long time I haven’t been able to fully live inside that identity — because the work of movement-building demanded something else from me. I was originally born in Ghana, raised largely in the Netherlands, and I’ve been here for almost 35 years. I’ve lived my adult life in this country. I know this country deeply — in many ways I know it more than Ghana, because this is where my children were born and raised, and where my community has had to fight for dignity in public, year after year.You said you’re a poet, but you’ve also been “occupied” by movement work for nearly two decades. How did that shift happen?From the age of 18, I started organising through an organisation I called So Rebel Movement. That was my starting point — and it was rooted in a very clear mentality: “for us, by us.” A Black-led, Black-guided movement that doesn’t ask permission to exist, and doesn’t need validation from outside the community. But the past 15 years became something else — a kind of intervention. The conditions became so urgent, and the pressure so constant, that I had to stop certain parts of my own life and “finish this job.” In many ways, I’m now returning to what I was always meant to be doing — but with lessons learned and scars that prove the cost of this work.Independence keeps coming up in your answers. What does independence mean to you in a Dutch context?My vision — whatever I do next — is to ensure I don’t need anything from the white community to make it happen. I’m very serious about that. For years, the work was focused outward: we were showing white Dutch society racism, discrimination, and the unfair treatment of Black people. That wasn’t because we wanted our lives to revolve around white people’s awareness — it was because the noise from that side was so loud that it blocked everything else. It was interfering with our ability to concentrate on what we wanted for ourselves.Now I feel like we have shut that noise down enough to get back to work. Because beyond the obstacles — yes, we know the obstacles — the most important question becomes: how do we overcome them by our own strength and our own means? I believe we already have everything we need to lift ourselves up. Sometimes we spend too much time seeking help where we don’t need help.Your movement is now dissolving. People might read that as “giving up.” How do you frame it?I frame it like work. If you’re working on a project and the project is finished, it’s finished. That doesn’t mean the whole world is suddenly perfect. It means you achieved the thing you set out to achieve — something big enough to matter, but not so abstract that it becomes a never-ending mission. We chose goals that were structural and measurable, so you could actually say: we did this. And now we can sign it off.So what were the goals — specifically — and why those?We had three goals. The first was structural education: colonial and slavery history in the curriculum. Before our movement, those were not meaningfully embedded the way they are now. Today, they are added.The second was education about racism itself — teaching about racism in schools. This was something we achieved together with another organisation, including a younger organisation that formed after the BLM demonstrations we organised here. It matters to me that younger people picked up momentum and built institutions of their own — because that’s also part of movement success: you don’t just win something, you create conditions for others to organise.The third was national commemoration. Fifteen years ago, many people didn’t know Keti Koti. Government funding had been cut down heavily — reduced to around 100,000 euros a year. Now it’s moving to 8 million euros per year going forward. And importantly: it’s not only to facilitate commemoration in the Netherlands. It also includes the Dutch Caribbean and Suriname — because our position was always: if something is gained here, those places must receive a fair share too. This is long overdue. And now the commemoration is nationally broadcast on TV and radio.When you say “it’s measurable,” what does it look like in real life?I’ll give you a simple example. Fifteen years ago, I would stand in front of classrooms and ask students: “Who has heard of Keti Koti?” Only a few hands would go up. Ask that question today — and all the hands go up. That’s a shift you can feel. It means the country cannot pretend anymore that it doesn’t know. Compare 2010 to 2025 and you can see the difference — not just in policy, but in public awareness. It’s visible.You also talk about the “noise” being shut down. Do you mean denial?Yes. Denial, dismissal, pretending it’s harmless, pretending it’s not racist — all the excuses. Our work forced the country to confront what it was doing. And once that confrontation happens at scale, it becomes harder to push the conversation back into silence.The Dutch king has apologised in multiple places and there’s research being done into royal involvement in slavery. How do you interpret that?It shows the scale of the shift. There are cities conducting research into their own involvement, writing reports, uncovering records. Because the truth is: the whole country profited from that history — or at least was complicit in it.These investigations matter because before, it took enormous energy from Black people just to start the conversation. When history is hidden, every conversation becomes a battle over “did it happen?” and “does it matter?” Bringing it to the surface opens the door to honest conversation beyond that.You said earlier: “removing ourselves is making space for the country.” Why step back now? Why not stay and keep pushing?Because part of movement maturity is knowing when your presence becomes the reason the conversation doesn’t evolve. If your movement is always the engine, the country can always blame you for “making a fuss.” But once those doors are open, and once the goals are achieved, stepping away forces the country to carry responsibility.Also, there’s the next generation. Our children — who are now adults — come with a different energy. They’ve seen that you can make a difference. They can choose what difference they want to make.Was there a moment where you had to decide what kind of movement you were building — reformist, revolutionary, something else?Yes, and it was painful. I had to ask myself: Do I want justice or do I want revenge? Because if I let anger lead me, my sight becomes blurry and my thinking becomes blurry. That caused heated discussions with people around me. Some people left because the backlash was too harsh, because they couldn’t handle the violence, because they had jobs and children and couldn’t risk it. Some people thought I was too soft. Others thought I was too radical.But I was always planning based on reality: how many people do we have, how far are they willing to go, what means do we have, what can we sustain? If we had declared “revolution” instead of fighting for pragmatic structural wins, it would have cost even more — and we might not have survived.What did you refuse to compromise on?Anything that kept even “a little Blackface.” Not acceptable. There were places that removed the entire figure. Others tried to keep things “close” to the racist element by using variations like “chimney” versions — anything that allowed them to stay emotionally attached to the caricature.But our view was: the solution is to move as far away from it as possible, so it’s not recognisable — because the harm is in the association. Children will make the comparison. They will confuse Black people for the caricature. That isn’t the child’s fault — it’s because society created a caricature and planted it everywhere.You keep returning to children. Why is that the centre?Because the tradition isn’t private — it’s national. It’s in schools, malls, streets, television, public space. People used to tell me stories of elders in their 60s, 70s, 80s who would avoid going outside during that period decades ago — only going out for work or groceries and then locking themselves in. Because the streets were full of people mimicking them, laughing at them, turning them into a public joke. That trauma sits in bodies for a lifetime.A lot of people remember the first time they realised they were Black. You don’t realise you are “other” until somebody others you. And being mocked publicly by both parents and children is one of the cruelest ways to learn that difference.What tactics actually worked over 15 years — if you had to explain your “method”?The biggest key is the first step: you take it, and you don’t stop. You keep going. But also: we diversified. Protest alone won’t get you there. Protest is a means, not the goal. We protested, created educational tools, built coalitions, had dialogues — even with people who attacked me. We didn’t start by begging politicians and media to take us seriously. We went to people in the streets first. The media found us before we even wrote a press release, because we were present — we were talking, confronting, insisting on the conversation where people were.I’ve spoken with thousands of people one-on-one over 15 years — almost every week, sometimes nearly every day. If you want real change, you have to be willing to do the unglamorous work.You also talk about allyship. How did you build coalitions without losing Black leadership?This is crucial: the movement began with around 90% Black people. Over time, more white people joined, and many Black people left — largely because the violence targeted Black participants most directly. So I made sure: even if I was the only Black person in the room, the movement stayed Black-led and Black-fronted. This country listens more easily to white people. But I refused to let white people become the face — because Black children needed to see Black people leading and holding ground.The allies who stayed understood that. They questioned me sometimes, but they gave me space to lead. And in return, it taught me something too: seeing white people committed to our success made me more committed to other struggles. That’s how solidarity should work.You mentioned a “price.” What did that price look like in reality?It cost a lot. People burned out. People lost jobs — including me. People were threatened. People were attacked. We were called terrorists. We were placed in a national terrorism report. There were years I wore a bulletproof vest.My life was on hold for 15 years. My daughter is 15 — born the same year the movement started. My son is 22 — he was around five or six when it started. I have never been on vacation with them. They went with their mother, but not with me. There were many nights I couldn’t be present the way a father should. That’s not something I say proudly — it’s something I say honestly, because people need to understand what “change” actually costs.But I also knew: the alternative is worse. How can I accept living in a country where, for two months every year, anti-Black racism is everywhere — on television, in streets, in schools, in malls — and people are having the best time of their life at our expense?How did you keep people safe in the face of intimidation and violence?My mindset was: we are fighting a war, and you have to be willing to lose something. That truth is what makes many people leave — and I understand why. But I also believed: none of those reasons would stop me.And I want to be clear: I never brought people into danger carelessly. I didn’t hide behind others. I took the biggest hit. And over time, I learned how to ask people to take what they could take — not more. But I also refused to “moderate” the truth for comfort. Either you are with us, or you are not.If you could demand one concrete policy action today, what would it be?There are two pathways. In the best case: from today onward, a truly fair system. Same treatment in court for the same crimes. Same support and safety for Black children and white children. Because right now you can predict a child’s future based on skin colour — and in a just country, you shouldn’t be able to do that. You are not God. You are not a magician. You can only predict because the system is designed to advantage one group and marginalise another.But if the country cannot or will not do that — then reparations must be paid to the direct descendants of enslaved people: people from the Dutch Caribbean and Suriname especially. They live with consequences that go beyond economics — even down to identity. Your surname is your address in the world. My name is Afriyie; you can trace where I come from. But many descendants of enslaved people carry names that only tie them to this soil — a soil that still treats them like guests, even after nearly 500 years. So either equality becomes real from now, or the country gives the descendants the means necessary to deal with the consequences of what was done.What does an “inclusive Sinterklaas” look like in practice — not just in theory?We confronted it directly in a Black neighbourhood in Amsterdam, and the authorities panicked and told us to find a solution. My view became: stop asking others to do it for us; we’ll create what we need.So we made a version where everyone is Sinterklaas — “Sinterklaas and his friends.” The children walking around were between four and twelve, all wearing Sinterklaas outfits. We gave them little sacks of candy — tiny hands holding the sacks — and some of them truly believed in the magic. Even after the event, they still believed. They’d hesitate like, “He’s here,” and we’d be like, “No, you’re walking for him now — go give out the candy.” It was joyful. No one was degraded. No one was harmed. That’s what inclusive means: a children’s celebration that is safe for all children to participate in or even just witness — without racism, stereotypes, or hierarchy built on servitude.You’re leaving behind resources. What are they, and why do they matter?Because a baton has to be passed, not dropped. When I came into this struggle, the baton wasn’t handed to me. I had to dig it up. That cost us time — at least five years — because we had to learn on the battlefield what could have been shared with us. So we’re making sure the next generation doesn’t lose time the way we did.We archived the movement carefully: documentation, photographs, records of actions, campaigns, and outcomes. We have educational tools and lesson plans. We’re finishing a teachers’ guide on confronting racism in the classroom. We built a history calendar with nearly 200 historical moments and figures the country should know, with sources and the ability for people to add events. We have an activist handbook that lays out what we learned — what you can expect, what you will face, and how to survive it. And we’re touring around the country with pop-up exhibitions and community dialogues — reflecting on the past 15 years and asking: when we step back, who keeps the marathon going?Before you ended the conversation, you added something personal about activism. Why was that important to say?Because while we demand that a country does better, we must also ask ourselves: where can we do better?I know I’m on the right side of history on racism — but what about women’s rights? Queer and trans rights? Indigenous rights? Disability rights? Palestine? How do we treat others? If you want your community to be safe, you must want every community to be safe. Don’t only call out injustice when it happens to you. Call it out when it happens to others. None of us are perfect. And real progress is collective progress.This is not the end — it is a handover. Visit the exhibition Netherlands, Do Better! – The Impact of 15 Years of Black Activism. Engage with the archives. Bring your students, colleagues, and communities. Study what worked. Learn what it costs. Decide what you will carry forward. Progress only survives when people choose to protect it. The baton is no longer in one movement’s hands — it is now in yours. And for those ready to step in even deeper: A super limited Patta x NLWB T-shirt will be available exclusively at the exhibition. Don’t miss out!Carry the work forward:https://neemhetstokjeover.nlhttps://nederlandwordtbeter.nlhttps://zwartmanifest.nl-

Get Familiar

-

-

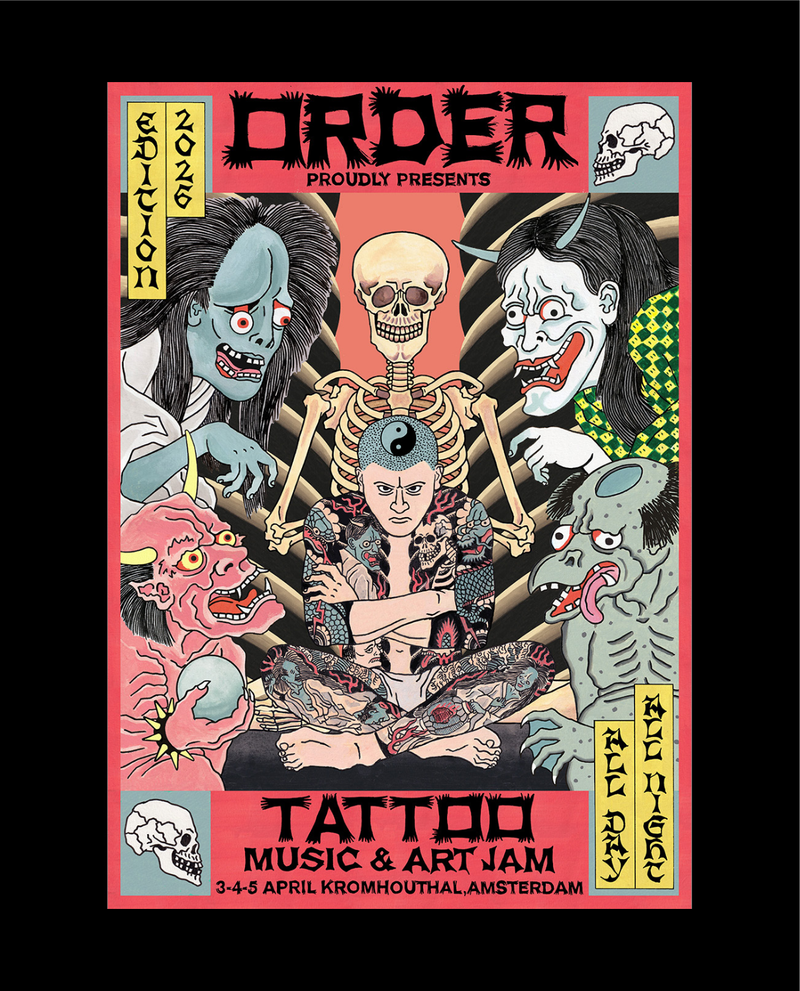

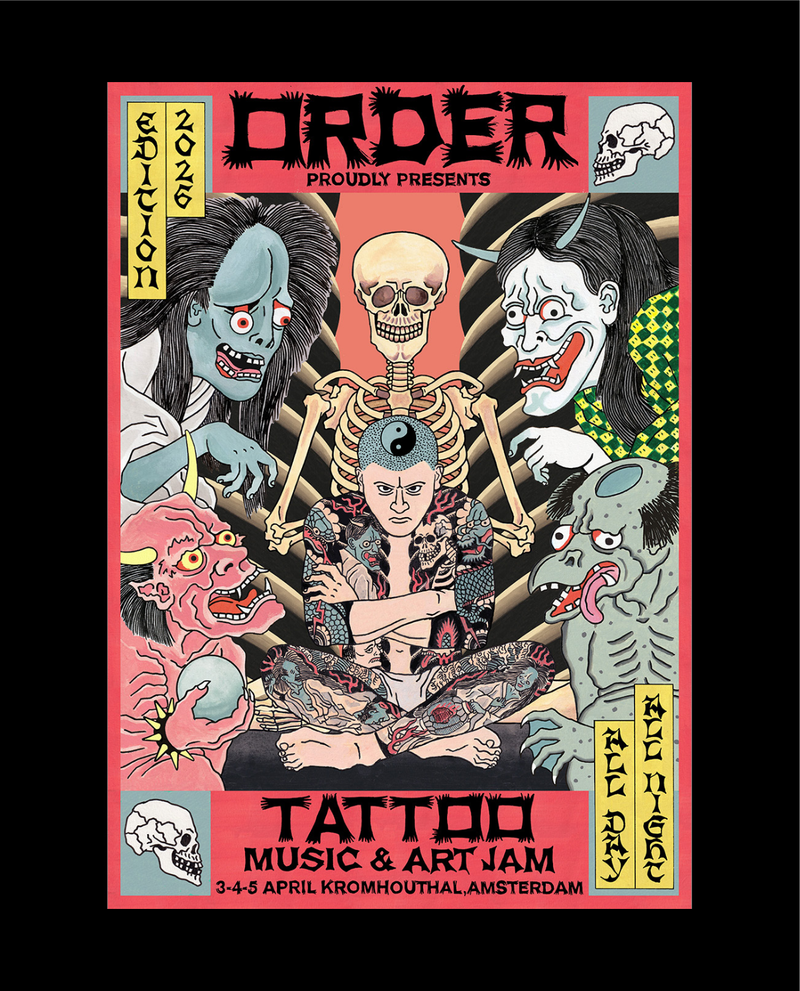

Order Tattoo, Music & Art Jam 2026

Order Tattoo, Music & Art Jam 2026

The 6th edition of Order Tattoo, Music & Art Jam is set to take over Amsterdam from Friday 3 April to Sunday 5 April 2026 — and this one will be bigger, louder and more alive than ever before. For three full days, tattooing, music, art and movement collide inside the brand-new Kromhouthal 231. With over 200 national and international tattoo artists, a buzzing Art Market, and a full food, drinks and entertainment zone, the Jam transforms the venue into a temporary world that only exists for one long weekend.Order Tattoo, Music & Art Jam has always been about community. This edition brings together artists, musicians, creatives, entertainers, crews, collectives and organisations such as Cantina, Sexyland, Skatecafé, Markt Centraal, Patta, No Limit Artcastle, TGIB, Atheneum News Center and many more. Everyone contributes to shaping something you won’t find anywhere else — a shared space where cultures overlap and creativity moves freely.The soundtrack of the weekend moves effortlessly between hip hop, rock, electro, punk, tropical heat and everything in between. Expect a dynamic mix of DJ sets, live bands and special performances that keep the energy high from opening until close, all weekend long. When the sun goes down, the Jam continues at Skatecafé, the place where it all started seven years ago. Just a three-minute walk from the Kromhouthal, Skatecafé hosts a major nightly party spread across four areas, filled with live music, performances and DJ sets. A separate ticket is required for the evening program and will be available online soon. The Kromhouthal is open to all ages. The evening program at Skatecafé is 18+ from 21:00 onwards.One of the heartbeats of the Jam is the Art Fair Market, featuring around 60 stands packed with art books, zines, prints, records, vintage finds, oddities and handmade goods. You’ll also find clothing, jewelry, nail art, grillz, a barber, tattoo suppliers and plenty more to explore. Right next door is the food, drinks and entertainment area — the perfect place to reset, chill or keep moving. Step outside to the beautiful waterfront area for fresh air and views across the water, with Central Station visible in the distance. All weekend long, step into the bold visual world of Deadly Prey: Ghana Movie Posters, a standout exhibition not to be missed.Tickets are available now.-

Events

-

-

What went down at Sounds Of Us

What went down at Sounds Of Us

Berlin, last dance of the year alongside Marshall and Mosiako. Conversations, connections, and soundtracks that shaped us — from panel to the boardgames to the dancefloor all documented by Andrea Amponsah. Thank you to everyone who pulled up and made it what it was. -

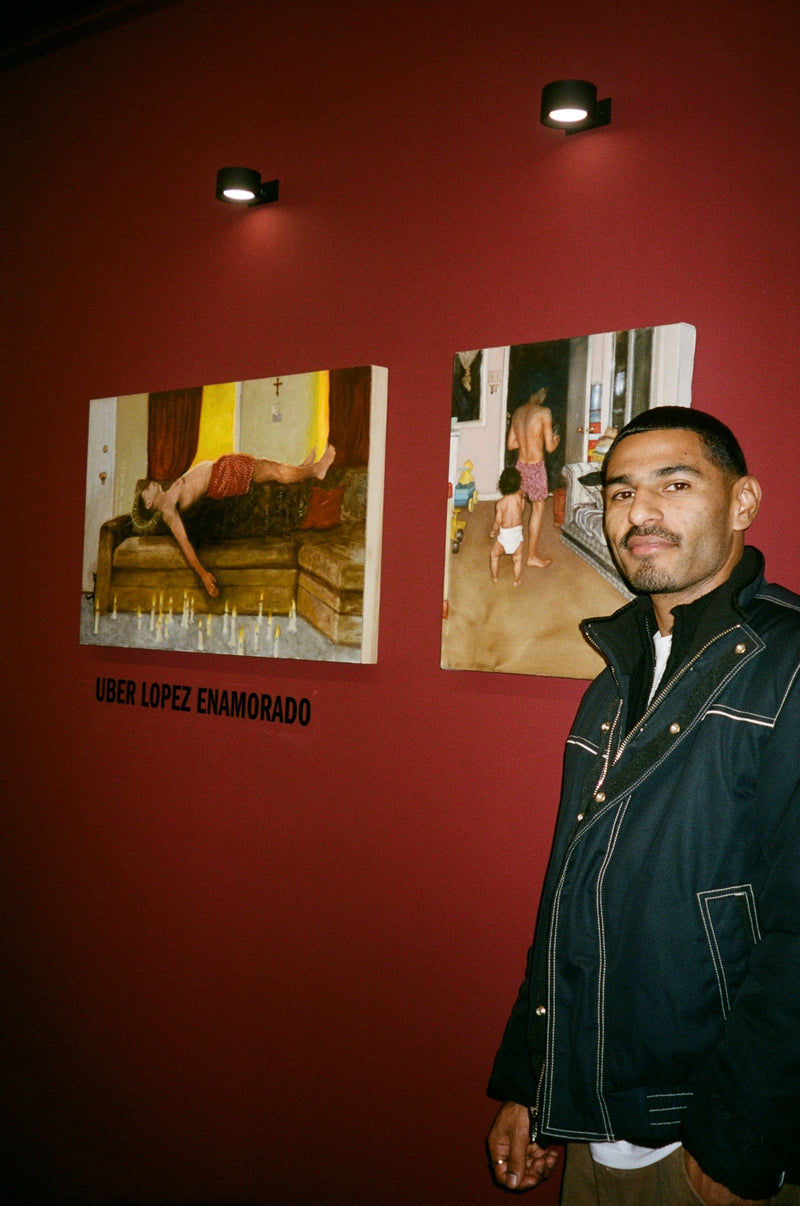

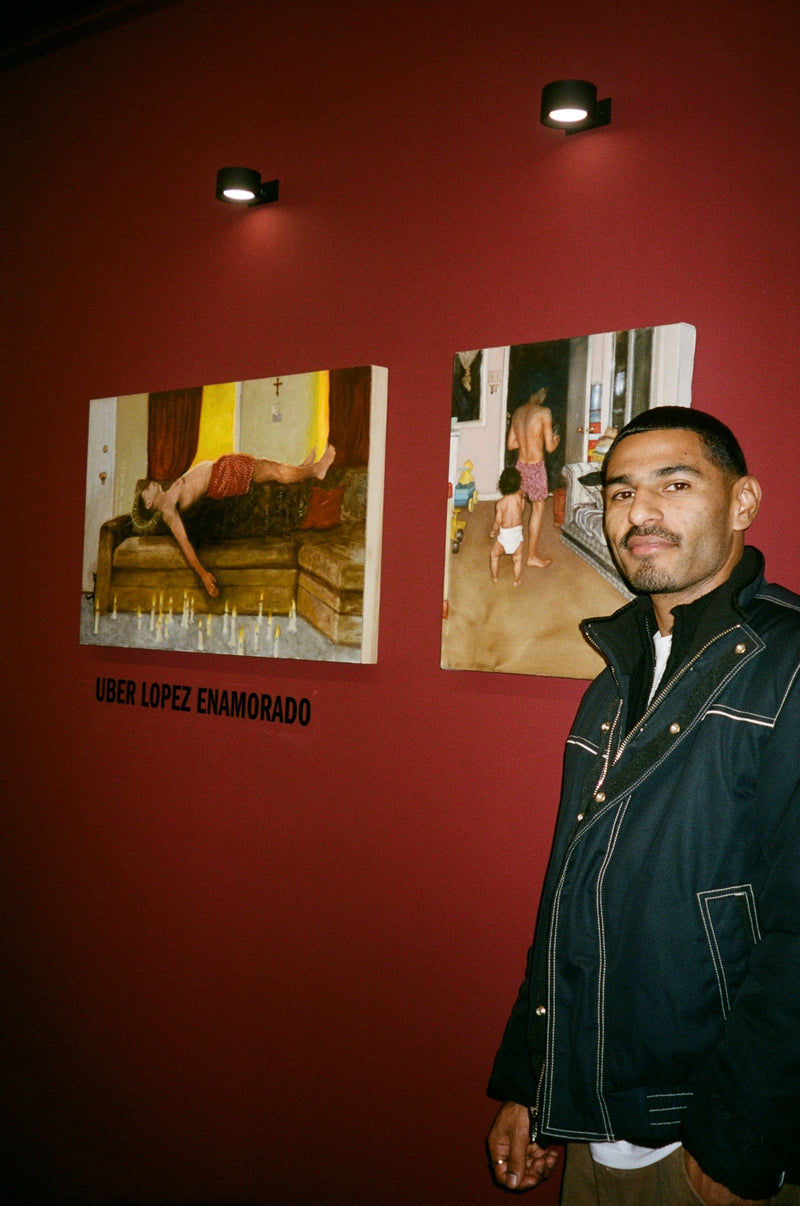

What went down at 1012 / 10012: Diasporic Iconographies

What went down at 1012 / 10012: Diasp...

Patta hosted the launch of 1012 / 10012: Diasporic Iconographies, an exhibition at Patta Amsterdam exploring shared visual languages across Surinamese and Latinx diasporas. Through imagery, symbolism and reinterpretation, the exhibition traces how culture travels, transforms and continues to shape identity across generations.The opening brought together community, creatives and collaborators for an intimate evening at the space — setting the tone for a weekend rooted in exchange, reflection and presence. From the works on display to the energy in the room, the launch marked a moment of convergence between histories, influences and lived experience.-

What Went Down

-

-

Get Familiar: Slimfit

Get Familiar: Slimfit

Interview by Passion DzengaRaised on soul, funk, punk, and the sounds of Suriname, Amsterdam-based artist Slimfit (Sammie Tjon Sien Foek) grew up in a home where The Cure played alongside Afrocaribbean classics, and LimeWire rabbit holes turned into early sonic education. Before ever stepping behind the decks, they were already building worlds—collecting obscure tracks, experimenting across disciplines, and shaping an ear sharpened by both Western and Afro diasporic influences.Their entry into Dutch nightlife came through Red Light Radio, a chance set that caught the right ears and opened the doors to Amsterdam’s rave ecosystem. From working the door at Garage Noord to becoming a fixture in contemporary club culture, Slimfit has always absorbed the scene from every angle. Today, their sets erupt with high-tempo emotion: Latin percussion, Afro-electronic rhythms, dramatic vocals, and a rave aesthetic that brings play, camp, and chaos back into techno’s often serious spaces.But Slimfit ticks many boxes—they’re a multidisciplinary artist, a thinker, and an advocate. Their work in nightlife is inseparable from their politics: pushing for equitable lineups, safer club environments, fairer fees, and solidarity structures that support marginalised communities. For them, sound is intuition, resistance, and connection all at once. In this conversation, Slimfit speaks about their roots, the evolution of the scene, and why the future of rave culture must be both louder and more caring.What music filled your home growing up?My dad—he’s Surinamese—played soul, funk, rap, the classics, plus Surinamese music. My mom was into The Cure and punk. I learned all the “golden oldies,” and as a teen, I dug deep on LimeWire and YouTube, hunting obscure tracks and making playlists in my room.Victor Crezée was one of the first to book you. What were those early experiences in Dutch nightlife and beyond?I started DJing about eight or nine years ago. One of my first breaks was a guest slot on Red Light Radio through a London–Amsterdam program. Vic heard that show, loved it, and connected me with Patta Soundxystem. Around the same time my first agent/manager, Mo, found me — I worked with him for many years, and he played a huge role in supporting and shaping my early trajectory. I got booked for Applesap, and I gradually shifted from a hip-hop/new wave/punk background into a more rave-leaning aesthetic. I also worked the door at Garage Noord for about a year—that scene shaped a lot of my influences.Why radio? Were you already making mixes?Totally—I had strong ideas about sets and mixes and kept building “potential” playlists from niche internet collectors. I was hungry for a radio show, had tons of music ready, and a clear concept of what I wanted people to hear. It happened to line up with Vic’s taste.You’re multi-disciplinary. Where does music sit among your practices?Everything I do is informed by sound—film, performance, graphic design, sound design. I studied photography and philosophy, but it all converges in audio. Sound is my intuition.Slimfit is the name people know you by in music, and your other work sits under your real name?Yes. I keep a portfolio under my own name (video, performance, design, drawings). I’m also finishing a master’s at the Sandberg Institute.How do you stay motivated across so much?I’m obsessed with getting what’s in my head into the world. I have scattered interests, constant inspiration, and a big ambition that keeps me moving—but I’m still learning how to pace myself and not do everything at once.Practical advice for artists trying to “do it all” and stay healthy?Sobriety (especially on the job) helps me stay clear. Surround yourself with grounded people who truly check in on you. I’ve just started going to the gym, and I meditate—my mom’s best friend is a Zen teacher, so I grew up around that. Finding silence amid subwoofers is key.You’ve become more socially engaged. Why do nightlife and activism merge for you?Club culture was built by people of colour seeking resistance and community. That political awareness is embedded in electronic music and rave spaces where initially marginalised identities used to gather for psychological relief and self-expression. My dad’s social work and left-wing politics background also shaped me. If we want safer, freer dance floors, we need to be politically aware and critical of the industry’s capitalist realities.What has changed in the scene since you started?It was very male-dominated; all-male lineups were normal. Awareness grew, and more women and people of colour got booked and curated—especially in the underground. There’s still work to do: commercial lineups often position POC people, queers, and women as openers. But we’re more than props for diversity — whole generations before us have built this scene.Can commercial ecosystems support underground/marginalised communities without tokenising them?No, I think that’s impossible if money pressures push events towards private equity and morally questionable financial partnerships. One alternative is building solidarity mechanisms into programming. During the KKR/Milkshake boycott (which I helped initiate alongside many artists and a broader movement), we launched RUIS—Reimagining Us in Solidarity—normalising fundraisers at larger events and proposing ethical advisory structures so donations are built into the night, not an afterthought.Are union-like structures part of the answer?Yes. With funding cuts and precarious nightlife economics, alternative organisation matters—mutual aid funds where artists contribute monthly and can draw support during illness or crisis. We need networks where artists can refuse exploitative money and still survive.Fees, fairness, and “artist care”?Equal-pay approaches simplify programming and reduce hypocrisy. If artist care is strong—dinners, mental-health spaces, genuine hospitality—you don’t need extreme fees to feel valued. Treat people like royalty and the money conversation gets easier.How important are safe spaces—both for you as a performer and a dancer?Non-negotiable. I can be expressive and sexy on stage, and I want femmes to dance freely without fear. If you do drugs, do it safely with people you trust. Dark rooms should be monitored. Unsafe spaces are traumatising—I don’t want to go back to that.Golden rules for keeping artists safe in the booth?Don’t touch without consent. Respect personal space and focus. Performing is part of my concentration—don’t ask for drink orders or requests mid-mix. Safety riders matter: have a manager check in every 20–30 minutes; deploy floor/club angels to monitor the crowd, especially when intoxication escalates behaviour.Is safety only the club’s job, or also the crowd’s?Everyone’s. Check on your friends; take them outside if needed. Hedonism can mask deeper issues. Community care reduces escalations.How would you describe your sound to someone who hasn’t seen you?High-tempo, emotive, harmony-driven, dramatic vocals, lots of rhythmic variety—Latin American and African diasporic influences (think neoperreo, gqom) woven into rave energy. I missed fun, camp, and hips in monotone techno, so I bring drama and play back into the rave. Outside the club, I love experimental/left-field—Arca, FKA twigs, even noise.Are you intentionally bridging serious techno spaces and playful queer energy?Yes. Purists safeguard culture, but artists can fuse worlds. I’ll play fast “TikTok-techno” rooms and slip in niche genres to widen ears—teaching through selection while being open to new iterations.Any anthems or artists that captured your story this year?Wanton Witch. She blends club, bass, and Asian tonalities in ways that resonate with my own Chinese-Creole roots—my great-grandfather moved from China to Suriname. Her tracks feel like that journey.How important is the representation of diasporas on the dance floor?Hearing your culture loud in a club is powerful. I try to program in ways that let people feel “seen” for a moment—like they’re the superstar.If Slimfit were a dish?A Sichuan dish—mouth-numbing, punchy, salty, spicy, refreshing.And if Slimfit scored a film?Under the Skin—a seductive, alien coming-of-age into something strange and monstrous. Luring you into an absurd world.-

Get Familiar

-